The Legacy of a Grandmother

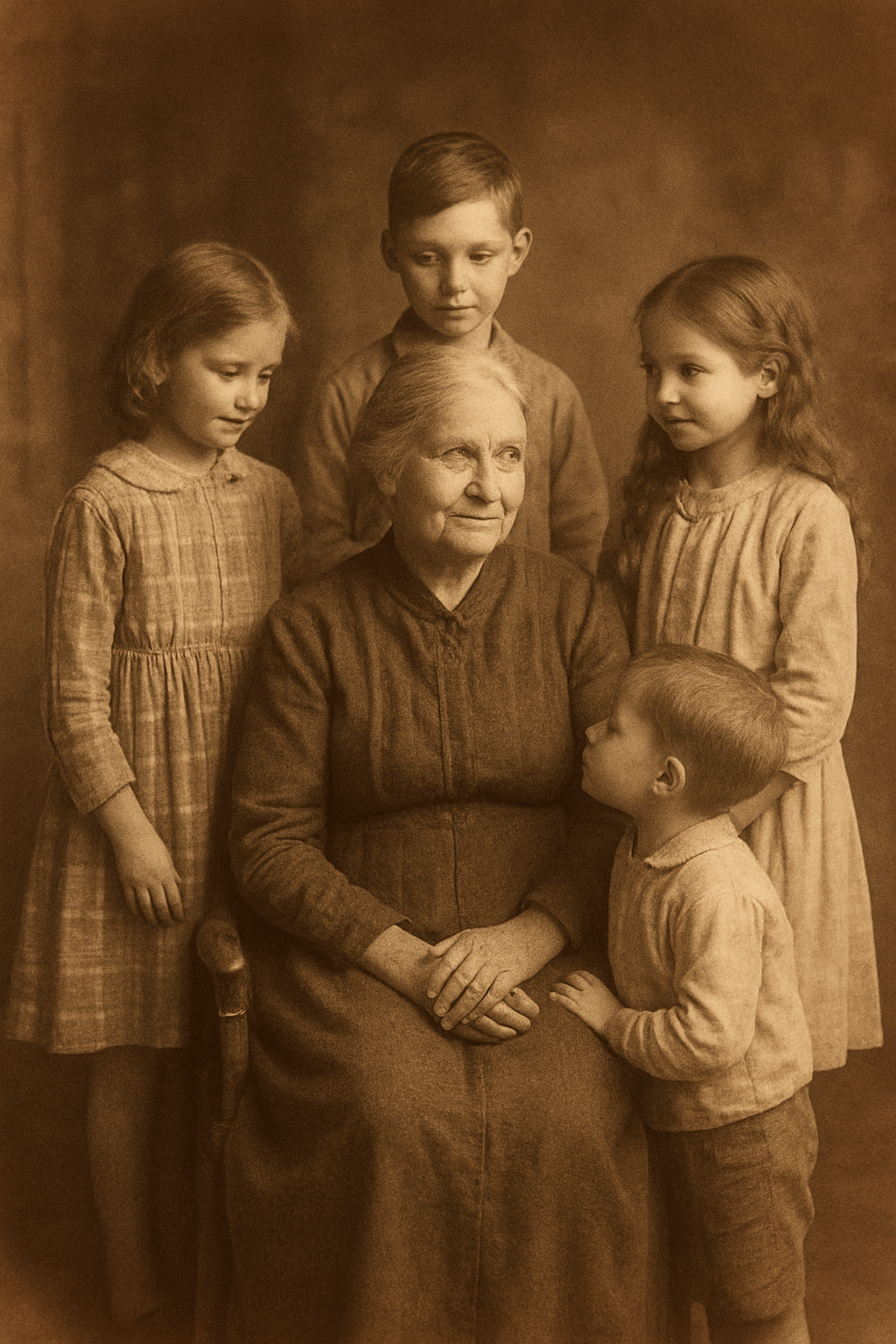

I had a grandma, a grandmom, and a nanna. Three very different women, born of different circumstances, and yet very much the same.

We lived with Nanna during my youngest years. Her home was a powerhouse of fond memories. She was a strong German woman who took in numerous foster children, one of whom was my mother. As an adult, my mom needed a wheelchair, and Nanna became partly her caretaker. As a child, I saw her as weak, but she was fierce in her strength.

Grandmom was my father’s mother, the daughter of a candymaker in Baltimore. She birthed thirteen children and had more grandchildren than anyone could count. I was one of them, yet when I was with her, she made me feel like the only one. Gentle and traditional, she baked the best cakes and grew the finest roses.

Grandma, my mother’s mother, lived on what we called “poverty row.” Her ex-husband, my grandfather, was abusive and an alcoholic, and a government agency split their three children apart. Fiercely religious and spiritual—a holy roller, a savior of the lost and downtrodden—she treated me like an angel. She laughed easily, knelt on my level, and helped pull me through the grief of losing Karen.

My mother, the grandmother of my children, spent most of her own childhood and teen years in the foster care system. Yet she became the most loving, involved grandmother of all. I was blessed with a model mother, and she carried that care into her role as “Grandma.”

Now it’s my turn. I carry forward elements of all four women, adding my own. I know some people never knew their grandmothers. Others may not have had positive experiences. But behind each of us is a legacy of women—whoever they were, however they lived—who shaped our lives.

Today, as I prepare for my grandson’s Wednesday visit, I feel those women with me—their laughter, their resilience, their love—woven into who I am as a grandmother.

What about you? What influence, positive or negative, did the women of the older generation leave on your life?