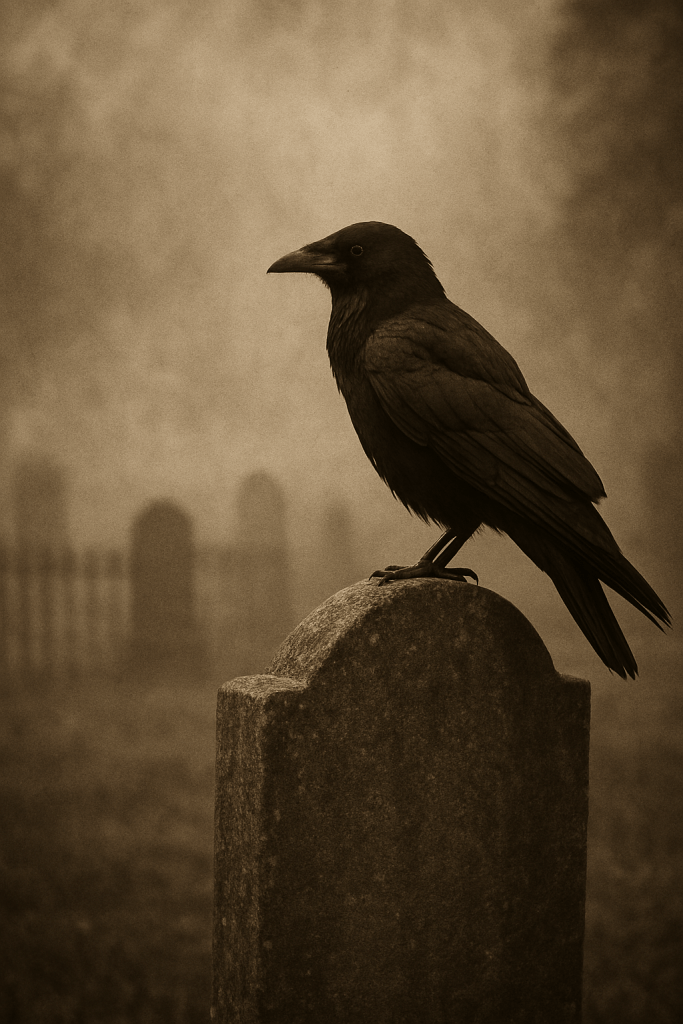

MEMENTO MORI- REMEMBER YOU MUST DIE

Call me morbidly curious, gothic—not goth, macabre, perhaps even a dark coper. They all mean about the same thing. Paraphrased from the dictionary, someone having a fascination for dark and unpleasant subjects, the supernatural, death, and melancholy. A dark coper, a person who uses scary media to process fear to gain a sense of preparedness for real-world dangers.

You would never know this looking at me. I don’t advertise. This leads me to a quandary: trying to explain my writing to people who view dark fiction (horror) as slasher movies and grotesque. Yes, there is a market for this type of film. It’s not my market, and it is definitely only a sub-genre of a vast cornucopia of artistic endeavors.

To me, a good dark fiction novel contains deep, well-rounded characters with strong arcs and meaningful relationships. They encounter, because of their own actions or the actions of someone or something else, a situation(s) leading them to a life and death situation. Physically or psychologically. A cause to reevaluate everything they thought they knew about life. A chance to make a difference. An opportunity to do the greater good—even if the result is self-sacrifice.

Yes, there are works of fiction where the antagonist is the main character. The twists and turns of a mind deliberately cause the protagonist to struggle. Even then, both the antagonist and the protagonist need to be well-rounded characters—why else would you root for success? Though in some situations, the result is disquieting as the antagonist wins, leaving the reader with their own sense of dread or self-evaluation. The Invasion of the Body Snatchers is a good example of this. Spoiler: the aliens win.

Someone asked me, “Why do you write horror? Why not write romance or dramas?”

All my novels contain historical drama and romance. However, my answer is simple. It’s a great way to have a safe place to explore fears and past traumas. It’s cathartic, entertaining. I like it when a character beats the odds and comes out whole. And of course, it harks back to Memento Mori. I’m drawn to it like a moth to a flame, unable to resist its calling. (Not today—at least I hope not!)

To date, I’ve written and self-published two fiction books. Death in Disguise is a dark murder mystery taking place in the 1950s in a small fictional town. The Revelation is a dark, supernatural tale set on an archaeological site in the 1980s. My latest finishedwork, currently vying for an agent, is called Dark Consequences, about an Irish famine victim, forced to come to America, where he makes a fateful decision bringing death to the small quarry community where he settles. It’s book one of a four-part series.

If you’re interested in well-developed characters living somewhere in history, a solid cast of characters and plots where the consequences of decisions are life-changing, exploring the world of the supernatural, give me a try. I’m really not that scary.